Quick Insights

- The Nibiru cataclysm is a conspiracy theory claiming a rogue planet, often called Nibiru or Planet X, will collide with or pass near Earth, causing catastrophic events.

- The theory originated from Zecharia Sitchin’s interpretations of ancient Mesopotamian texts, suggesting Nibiru orbits the Sun every 3,600 years.

- NASA and other scientific bodies have repeatedly debunked the existence of Nibiru, stating no evidence supports a large planet threatening Earth.

- Predictions of Nibiru’s arrival have been made for decades, with specific dates like September 23, 2017, and April 23, 2018, passing without incident.

- Conspiracy theorists claim Nibiru’s gravitational pull could trigger earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and pole shifts, but scientists say such a planet would be visible if it existed.

- The Nibiru theory often merges with other doomsday scenarios, including biblical prophecies and pseudoscientific claims about solar activity.

What Are the Origins and Claims of the Nibiru Theory?

The Nibiru cataclysm theory posits that a massive, undiscovered planet called Nibiru or Planet X follows a long, elliptical orbit around the Sun, bringing it close to Earth every few thousand years. This idea stems from the works of Zecharia Sitchin, who in the 1970s interpreted ancient Sumerian texts to suggest Nibiru was home to an extraterrestrial race called the Anunnaki. Sitchin claimed these beings visited Earth in antiquity, influencing human civilization. The modern conspiracy theory, however, focuses on catastrophic consequences, alleging that Nibiru’s gravitational pull could cause earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and even a magnetic pole shift. Proponents like Nancy Lieder, who claimed to channel aliens from the Zeta Reticuli star system, have predicted specific dates for Nibiru’s arrival, such as May 2003, which was later revised. These predictions often gain traction online, amplified by YouTube channels and fringe websites like Before It’s News. Despite its popularity, the theory lacks any observational evidence. Astronomers argue that a planet of Nibiru’s supposed size—often described as larger than Jupiter—would be detectable by telescopes long before approaching Earth. The theory’s persistence reflects a broader fascination with apocalyptic scenarios, often tied to distrust in scientific institutions. Critics note that Nibiru’s narrative shifts with each failed prediction, adapting to new astronomical discoveries or global events.

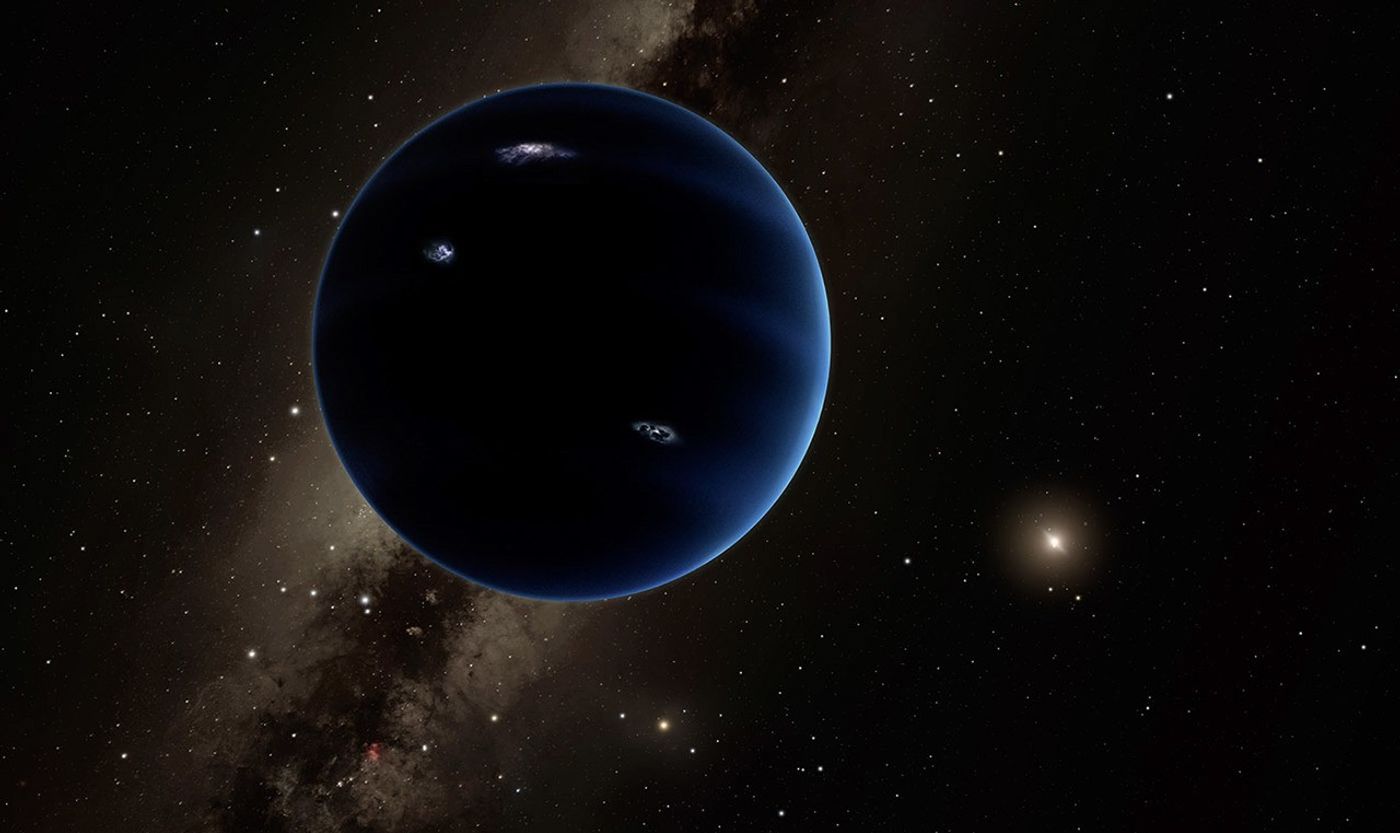

The Nibiru theory has also been linked to real scientific searches for undiscovered planets, such as Planet Nine, a hypothetical body in the outer solar system proposed by Caltech researchers in 2016. Unlike Nibiru, Planet Nine is theorized to have an orbit far beyond Neptune, with no threat to Earth. Conspiracy theorists, however, conflate the two, using scientific findings to lend credibility to their claims. This blending of fact and fiction has fueled media coverage, with outlets like Express.co.uk reporting on alleged Nibiru sightings, such as a 2017 video claiming to show a meteor from the Nibiru system. These reports are often debunked as misidentified meteors or optical illusions. The theory’s appeal lies in its ability to connect unrelated phenomena—natural disasters, biblical prophecies, or unusual sky events—into a single narrative. Social media platforms, particularly X, have amplified these ideas, with posts claiming Nibiru is visible or causing climate changes. Yet, no credible astronomical data supports these assertions. The theory’s resilience highlights the challenge of countering misinformation in the digital age.

What Is the Historical and Cultural Context of the Nibiru Theory?

The Nibiru cataclysm theory draws from a mix of ancient mythology, modern pseudoscience, and cultural anxieties about the end of the world. Zecharia Sitchin’s books, starting with The 12th Planet in 1976, laid the groundwork by interpreting Sumerian cuneiform texts as evidence of an advanced alien civilization from Nibiru. These claims, while dismissed by mainstream scholars, resonated with audiences seeking alternative explanations for human history. The theory gained momentum in the late 1990s and early 2000s, particularly through Nancy Lieder’s website, which predicted a 2003 cataclysm. This period coincided with growing interest in apocalyptic scenarios, fueled by the Y2K panic and later the 2012 Mayan calendar predictions. The Nibiru narrative absorbed these cultural currents, linking itself to biblical prophecies like the Book of Revelation or the concept of Wormwood, a star said to herald destruction. By the late 2000s, the theory had become a staple of online conspiracy communities, often tied to distrust in government and scientific institutions. Media outlets, including tabloids like Express.co.uk, capitalized on this interest, publishing sensational claims about Nibiru’s imminent arrival. These stories often cite unverified sources, such as alleged whistleblowers or amateur astronomers, to stoke fear and curiosity. The theory’s cultural impact lies in its ability to adapt to new contexts, from comets like Elenin in 2011 to the 2017 solar eclipse.

Historically, doomsday predictions are not new. From ancient prophecies to modern cults, societies have long been fascinated by the idea of a cosmic or divine reckoning. The Nibiru theory fits this pattern, blending ancient myths with contemporary fears about climate change, geopolitical instability, and technological disruption. Its proponents often point to natural disasters—like earthquakes in Indonesia or volcanic activity—as evidence of Nibiru’s influence, despite scientific explanations attributing these to plate tectonics or weather patterns. The theory also reflects a broader skepticism toward expertise, with some believers accusing NASA of a cover-up. This distrust peaked in 2017 when conspiracy theorist David Meade predicted a September 23 cataclysm, citing biblical numerology and celestial alignments. When the date passed uneventfully, Meade revised his prediction to November 19, illustrating the theory’s flexibility in the face of disconfirmation. The Nibiru narrative thrives in online echo chambers, where videos and posts on platforms like YouTube and X garner millions of views. Its persistence underscores the human tendency to seek meaning in chaos, even when evidence is absent. The theory’s cultural staying power suggests it will continue to resurface, tied to new events or discoveries.

What Are the Key Arguments For and Against the Nibiru Theory?

Proponents of the Nibiru cataclysm argue that the planet’s existence is supported by ancient texts, unusual astronomical phenomena, and alleged government cover-ups. They claim Sumerian records describe a massive planet with a 3,600-year orbit, a narrative popularized by Sitchin’s work. Figures like David Meade and Yuval Ovadia assert that recent natural disasters, such as earthquakes or hurricanes, are caused by Nibiru’s gravitational pull as it approaches the inner solar system. They point to videos of bright objects in the sky, like a 2017 Bermuda fireball, as evidence of Nibiru or its debris. Some believers, including Gordon James Gianninoto, argue that Nibiru’s influence extends to electromagnetic disruptions, potentially mimicking an EMP bomb. They also claim NASA and other agencies suppress evidence to avoid public panic, citing alleged secret observatory footage or whistleblower accounts. These arguments often blend biblical prophecy, such as the Book of Revelation, with pseudoscientific claims about pole shifts or solar activity. Social media platforms like X amplify these ideas, with users sharing supposed sightings or warnings of imminent catastrophe. The theory’s proponents remain undeterred by failed predictions, often revising dates or reinterpreting events to fit their narrative. This adaptability keeps the theory alive despite repeated debunkings.

Scientists, including NASA’s David Morrison and physicist Brian Cox, counter that no evidence supports Nibiru’s existence. They argue that a planet large enough to cause catastrophic effects would be visible to the naked eye or detectable by telescopes long before reaching Earth. Morrison has emphasized that no astronomical observations—whether from professional observatories or amateur astronomers—show a rogue planet in the solar system. The search for Planet Nine, a scientifically grounded hypothesis, is often misused by Nibiru proponents, but its proposed orbit is far too distant to affect Earth. Critics also note that the theory relies on misinterpretations of Sumerian texts, which mainstream scholars say do not describe a planet like Nibiru. Failed predictions, such as those for 2003, 2012, 2017, and 2018, undermine the theory’s credibility, as no catastrophic events occurred. Scientists attribute natural disasters to well-understood causes like tectonic activity, not a hidden planet. NASA has issued multiple statements dismissing Nibiru as an internet hoax, pointing out that its supposed effects, like pole shifts, are physically implausible. Debunkers like Scott Brando, who runs ufoofinterest.org, have shown that alleged Nibiru sightings are often meteors, contrails, or optical illusions. The scientific consensus is clear: Nibiru is a myth with no basis in observable reality.

What Are the Ethical and Social Implications of the Nibiru Theory?

The Nibiru cataclysm theory raises ethical concerns about the spread of misinformation and its impact on public perception. By promoting unverified claims, conspiracy theorists can sow fear and anxiety, particularly among those already distrustful of institutions. Sensational media coverage, such as articles from Express.co.uk or Before It’s News, often amplifies these fears for clicks or ad revenue, prioritizing profit over accuracy. This can erode trust in science, as believers accuse NASA and other agencies of cover-ups, fostering a broader anti-expertise sentiment. The theory’s reliance on pseudoscience also risks diverting attention from real issues, like climate change or disaster preparedness, which require evidence-based solutions. For individuals, the constant cycle of doomsday predictions can lead to psychological stress or fatalism, with some preparing for nonexistent threats instead of addressing tangible concerns. The ethical responsibility of media and online platforms to moderate such content remains a contentious issue, as free speech clashes with the harm of misinformation. Socially, the theory exploits cultural fears about the unknown, tapping into anxieties about global instability. It also highlights the digital divide, as those with limited access to reliable information may be more susceptible to fringe narratives. The Nibiru phenomenon underscores the need for better science communication to counter misinformation effectively.

The social impact of the Nibiru theory extends to its role in online communities, where it fosters a sense of shared identity among believers. Platforms like X and YouTube allow rapid dissemination of unverified claims, creating echo chambers where dissent is dismissed as part of a conspiracy. This dynamic can isolate individuals from mainstream discourse, reinforcing distrust in authorities. The theory’s appeal often lies in its apocalyptic narrative, which offers a simple explanation for complex global problems. However, this can lead to real-world consequences, such as panic or misguided actions, as seen in past doomsday cults. Ethically, scientists and educators face the challenge of engaging with believers without dismissing their concerns outright, as ridicule can entrench their views. The Nibiru theory also reflects broader societal tensions, including skepticism toward globalization and centralized authority. Its persistence suggests a need for media literacy programs to help people evaluate sources critically. By addressing these underlying issues, society can mitigate the harm of such conspiracy theories. The Nibiru narrative serves as a case study in how fear-driven stories can spread in the digital age, shaping perceptions and behaviors in ways that demand careful consideration.

What Does the Nibiru Theory Mean for the Future?

The Nibiru cataclysm theory is unlikely to disappear, given its adaptability and appeal to those seeking alternative explanations for global events. As new astronomical discoveries, like the ongoing search for Planet Nine, emerge, conspiracy theorists may continue to co-opt them to revive Nibiru claims. Future predictions, such as those suggesting a 2060 flyby, indicate the theory’s ability to project doomsday far enough to maintain intrigue without immediate disproof. The spread of misinformation on platforms like X suggests that social media will remain a key driver, with algorithms amplifying sensational content. This could exacerbate public distrust in science, particularly as real challenges like climate change demand collective action. The theory’s future iterations may also incorporate emerging technologies, such as AI-generated images or videos, to create more convincing “evidence” of Nibiru. Governments and scientific institutions will need to counter this with proactive communication, emphasizing transparency and accessibility. The persistence of such theories highlights the importance of addressing underlying social anxieties, such as economic uncertainty or environmental fears, that fuel apocalyptic narratives. Without such efforts, Nibiru and similar conspiracies will continue to thrive in online spaces. The challenge lies in balancing open dialogue with the need to curb harmful misinformation.

Looking ahead, the Nibiru theory could influence how society approaches science education and public trust. Schools and universities may need to prioritize critical thinking and media literacy to equip people to distinguish fact from fiction. Scientists like David Morrison, who have spent years debunking Nibiru, highlight the burden on experts to engage with the public patiently. The theory’s future also depends on how platforms like X and YouTube address misinformation, whether through content moderation or promoting credible sources. If left unchecked, Nibiru-like narratives could undermine efforts to address real cosmic threats, such as asteroid impacts, which NASA actively monitors. The theory’s cultural staying power suggests it will resurface with new dates or events, such as solar eclipses or natural disasters. Addressing this requires a multifaceted approach, combining education, transparent science communication, and responsible journalism. The Nibiru phenomenon serves as a warning of how unverified claims can shape public perception, potentially distracting from pressing global issues. Its future impact will depend on society’s ability to foster trust and critical inquiry in an era of information overload. The ongoing challenge is to ensure that evidence-based reasoning prevails over fear-driven speculation.

Conclusion and Key Lessons

The Nibiru cataclysm theory, despite its lack of scientific evidence, continues to captivate audiences due to its blend of ancient mythology, apocalyptic fears, and distrust in institutions. It originated from Zecharia Sitchin’s interpretations of Sumerian texts and has been fueled by online platforms and sensational media. Scientists, including NASA’s David Morrison, have consistently debunked Nibiru, emphasizing that no observable planet threatens Earth. The theory’s persistence reflects cultural anxieties and the power of digital echo chambers to amplify misinformation. Proponents argue it explains natural disasters and celestial events, while critics point to the absence of astronomical evidence and the theory’s repeated failed predictions. Ethically, the spread of such claims raises concerns about media responsibility and public trust in science.

Key lessons include the need for robust science communication to counter misinformation effectively. Media literacy programs can help individuals evaluate sources critically, reducing the appeal of conspiracy theories. The Nibiru phenomenon underscores the importance of addressing societal fears that fuel apocalyptic narratives. Scientists and educators must engage with the public transparently to rebuild trust. The theory’s future lies in its ability to adapt to new events, highlighting the ongoing challenge of combating misinformation in the digital age. Society must prioritize evidence-based reasoning to address real challenges, from climate change to cosmic threats, without being distracted by unverified claims.

Disclaimer: This article examines controversial theories and claims for educational purposes. Content does not constitute scientific or theological advice. Many theories discussed are rejected by mainstream science and lack empirical evidence. Think critically and conduct independent research. Questions? Contact editor@amen4jesus.com