Quick Insights

- The Hollow Earth theory suggests that the planet is not solid but contains vast interior spaces, possibly inhabited by advanced civilizations or beings.

- Historical proponents, like Edmond Halley in the 17th century, proposed the Earth might consist of concentric spheres with habitable interiors.

- Modern science, including seismic studies and gravity measurements, finds no evidence to support the idea of a hollow Earth.

- Stories of Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s polar expeditions in the 1920s and 1940s fuel speculation, though his official records do not mention inner civilizations.

- Ancient myths and modern conspiracy theories, including tales of Agartha, keep the idea alive despite scientific rejection.

- Recent discussions on platforms like X highlight ongoing fascination, but no credible evidence has emerged to support the theory.

What Are the Core Claims of the Hollow Earth Theory?

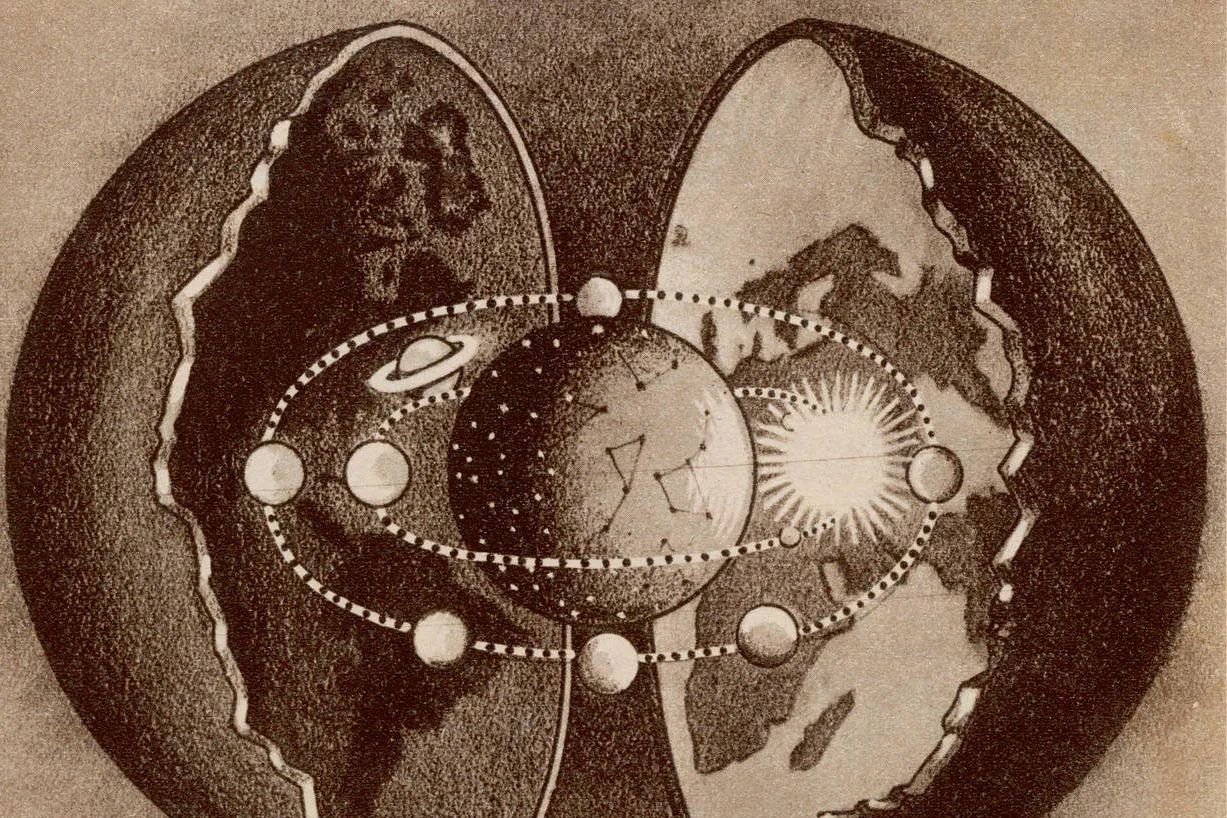

The Hollow Earth theory posits that the Earth is either entirely hollow or contains significant interior spaces capable of supporting life. This idea dates back centuries, with early proponents like English astronomer Edmond Halley suggesting in 1692 that the Earth might consist of nested spheres with a luminous atmosphere inside. In the 19th century, John Cleves Symmes Jr. expanded on this, claiming the Earth had openings at the poles leading to a habitable interior. Some versions of the theory describe a central sun illuminating these spaces, sustaining ecosystems or advanced civilizations like the mythical Agartha. These claims often draw from ancient legends across cultures, such as Tibetan Buddhism’s Shambhala or Greek myths of underworld realms. Proponents argue that anomalies, like unusual magnetic readings or obscured satellite imagery at the poles, hint at hidden entrances. Others point to alleged eyewitness accounts, such as those attributed to Admiral Richard E. Byrd, who reportedly described lush landscapes inside the Earth during his polar expeditions. However, these accounts, particularly Byrd’s supposed diary entries, lack verification and are widely considered fictional. The theory also suggests that governments or organizations like NASA suppress evidence to conceal the truth about these subterranean worlds. Despite its allure, the theory remains a fringe concept, with no peer-reviewed studies supporting its claims.

The persistence of the Hollow Earth theory stems from a mix of historical speculation and modern conspiracy culture. For example, some proponents cite the discovery of underground water reservoirs, like Lake Vostok in Antarctica, as evidence of large cavities within the Earth. Others reference ancient sites like Derinkuyu in Turkey, an underground city from the 7th or 8th century BCE, as proof of subterranean habitation. These examples, however, align with known geological and archaeological findings rather than a hollow planet. The theory’s appeal lies in its ability to blend myth, science fiction, and distrust in official narratives. Online discussions, particularly on platforms like X, often amplify these ideas, with users sharing unverified stories of polar entrances or advanced beings. Yet, the lack of tangible evidence, such as photographs or physical artifacts, undermines these claims. The theory’s reliance on anecdotal accounts and speculative interpretations of scientific data keeps it outside mainstream acceptance. Its cultural significance, however, cannot be dismissed, as it reflects humanity’s curiosity about the unknown. This fascination drives continued interest, even as scientific consensus rejects the possibility of a hollow Earth.

What Historical Context Shapes the Hollow Earth Narrative?

The Hollow Earth theory has roots in both scientific speculation and cultural storytelling. In 1692, Edmond Halley, known for his work on comets, proposed that the Earth might consist of concentric spheres, possibly habitable, to explain anomalies in magnetic fields. His hypothesis was grounded in the limited scientific understanding of the time, before modern geology clarified the Earth’s layered structure. By the 19th century, John Cleves Symmes Jr. popularized the idea of polar openings, advocating for expeditions to explore these supposed gateways. His ideas influenced literature, inspiring works like Jules Verne’s A Journey to the Center of the Earth in 1864, which blended science and fantasy. Ancient myths also shaped the narrative, with cultures like the Greeks describing underworlds ruled by gods like Hades, and Tibetan Buddhists referencing Shambhala, a hidden kingdom of wisdom. These stories provided a foundation for later theories about subterranean civilizations. In the early 20th century, occultists like Helena Blavatsky integrated Hollow Earth ideas into esoteric teachings, linking them to ancient races and mystical knowledge. This blend of science, myth, and spirituality gave the theory a broad cultural footprint. By the mid-20th century, conspiracy theories added new layers, with claims that governments hid evidence of inner worlds to maintain control.

The theory gained traction during times of scientific and political upheaval. For instance, during the Cold War, stories of Admiral Byrd’s expeditions were repurposed to suggest he discovered entrances to a hidden world, though his official reports mention no such findings. The Nazi regime’s interest in esoteric ideas also fueled speculation, with some claiming they sought Agartha as a refuge for Hitler. These historical connections highlight how the theory thrives in environments of distrust or uncertainty. Archaeological discoveries, like the underground cities of Cappadocia, have been misinterpreted as evidence of vast subterranean realms, despite being explainable as human-made shelters. The 20th century saw the theory evolve with UFO lore, as some suggested extraterrestrials originated from inside the Earth rather than outer space. This adaptability has kept the Hollow Earth concept alive, even as scientific advancements, like seismic imaging, disprove its core claims. The interplay between historical exploration, mythology, and modern skepticism continues to shape its enduring appeal. Today, online platforms amplify these ideas, with users citing unverified sources to argue for hidden truths. This historical context shows why the theory persists, despite lacking empirical support.

What Are the Key Arguments For and Against the Theory?

Advocates of the Hollow Earth theory argue that certain anomalies support the existence of a hidden interior. They point to unusual magnetic and gravitational readings at the poles, suggesting these could indicate voids or less dense regions beneath the surface. Some reference discoveries like ringwoodite, a mineral containing water deep in the Earth’s mantle, as evidence of vast underground reservoirs that might sustain life. Eyewitness accounts, such as those attributed to Admiral Byrd, are often cited, with proponents claiming he saw lush landscapes and advanced civilizations during his polar flights. Others argue that ancient myths across cultures, from the Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh to Hindu texts like the Ramayana, consistently describe subterranean worlds, hinting at a shared truth. Conspiracy theorists suggest that governments obscure satellite imagery or restrict polar exploration to hide entrances to these realms. The discovery of microbial life deep underground, like in Western Australia’s Pilbara Craton, is sometimes used to argue that complex ecosystems could exist in uncharted cavities. Proponents also claim that the Earth’s gravity would be weaker if it were hollow, interpreting this as a possible explanation for certain unexplained phenomena. The theory’s appeal lies in its challenge to mainstream science, offering a narrative of hidden knowledge. These arguments, however, rely heavily on speculation and unverified claims.

Opponents, including most scientists, argue that the Hollow Earth theory contradicts well-established evidence. Seismic studies, which track earthquake waves through the Earth, confirm a layered structure with a solid mantle, outer core, and inner core. These waves would behave differently in a hollow planet, yet data consistently supports a solid Earth. Gravity measurements also indicate a dense interior, as a hollow Earth would result in weaker gravity, incompatible with observed values. Satellite imagery and polar expeditions have found no evidence of large openings at the North or South Poles, as some theories claim. Geological studies, including core samples and drilling projects, reveal no vast cavities capable of supporting civilizations. Claims about Byrd’s expeditions are dismissed, as his verified records contain no mention of inner worlds, and alleged diaries are considered hoaxes. Ancient myths, while culturally significant, are seen as symbolic rather than literal. Critics also note that conspiracy claims about suppressed evidence lack substantiation, as scientific data is openly published. The consensus is that the theory thrives on imagination rather than facts, with no credible evidence to challenge modern geology.

What Are the Ethical and Social Implications of the Theory?

The Hollow Earth theory, while scientifically discredited, raises ethical questions about the spread of unverified information. Its persistence in popular culture and online communities reflects a broader societal distrust in institutions like science and government. This skepticism can foster critical thinking but also risks promoting misinformation when unproven claims are presented as truth. For example, conspiracy narratives about NASA or global cover-ups can erode public trust in credible research, diverting attention from real scientific challenges. The theory’s romanticized view of hidden civilizations, like Agartha, can inspire creativity in literature and media but may also exploit cultural myths for sensationalism. Ancient stories, such as those of Shambhala, hold spiritual significance for some communities, and their use in fringe theories could be seen as disrespectful. Socially, the theory appeals to those seeking alternative explanations for the world, often in times of uncertainty or disenfranchisement. Online platforms like X amplify these ideas, creating echo chambers where unverified claims gain traction without scrutiny. This dynamic highlights the need for better science communication to bridge gaps between experts and the public. Ethically, proponents must consider the impact of spreading unverified narratives, especially when they challenge established knowledge without evidence.

The theory also touches on cultural fascination with the unknown, which can be both inspiring and problematic. It encourages imagination, as seen in works like Jules Verne’s novels, which captivate readers with tales of hidden worlds. However, when taken literally, it can lead to misguided efforts, such as expeditions to find polar entrances, wasting resources and potentially endangering lives. The association of the theory with fringe groups, like those claiming Nazi connections to Agartha, risks normalizing extremist ideologies under the guise of exploration. Socially, the theory’s appeal reflects a human desire to question reality, but it also underscores the importance of critical literacy in evaluating sources. The ethical responsibility lies in balancing open inquiry with accountability for claims that lack evidence. For instance, citing unverified accounts, like Byrd’s alleged diaries, without acknowledging their dubious nature can mislead audiences. The theory’s cultural impact, while significant, requires careful navigation to avoid distorting historical or scientific truths. Addressing these implications calls for dialogue between skeptics and believers to foster understanding without dismissing curiosity. This balance is crucial in a digital age where ideas spread rapidly.

What Could the Future Hold for Hollow Earth Beliefs?

The future of the Hollow Earth theory likely depends on the interplay between scientific advancements and cultural trends. As technology improves, tools like advanced seismic imaging or deep-drilling projects could further debunk the idea by mapping the Earth’s interior with greater precision. Discoveries of underground ecosystems, such as microbial life in extreme environments, may fuel speculation, but these align with known science rather than hollow Earth claims. Public interest in the theory may persist, driven by media like documentaries or fictional works that romanticize hidden worlds. Platforms like X will continue to amplify discussions, with users sharing theories about polar anomalies or government cover-ups. However, without credible evidence, the theory is unlikely to gain mainstream acceptance. Educational efforts to explain geological science could reduce its appeal, though entrenched distrust in institutions may sustain belief among some groups. The theory’s adaptability, seen in its incorporation of UFOs or ancient aliens, suggests it will evolve to fit new cultural narratives. Future expeditions to remote areas, like Antarctica, might reignite speculation if anomalies are found, but current data leaves little room for such claims. The challenge lies in addressing curiosity without dismissing it outright, as outright rejection can entrench conspiracy beliefs.

Looking ahead, the Hollow Earth theory may serve as a case study in how pseudoscience persists in the digital age. Its allure lies in its ability to tap into human wonder, much like myths of Atlantis or extraterrestrial life. Advances in science communication, such as interactive visualizations of Earth’s structure, could help demystify the planet’s interior for the public. Meanwhile, the theory’s cultural impact will likely endure in fiction, inspiring stories of hidden realms. Socially, it may continue to attract those skeptical of official narratives, particularly in polarized times. The ethical challenge will be fostering open dialogue while grounding discussions in evidence. If new discoveries, like vast underground cavities, emerge, they could be misinterpreted as supporting the theory, necessitating clear communication from scientists. Ultimately, the theory’s future depends on balancing human curiosity with rigorous inquiry. Its persistence underscores the need for education that encourages questioning while equipping people to evaluate claims critically. The Hollow Earth narrative, while unlikely to be proven, will remain a fascinating lens into human imagination and skepticism.

Conclusion and Key Lessons

The Hollow Earth theory, despite its lack of scientific support, remains a captivating idea that blends ancient myths, historical speculation, and modern conspiracy culture. It draws from early scientific hypotheses, like those of Edmond Halley, and cultural stories of subterranean realms, but seismic data, gravity measurements, and polar explorations confirm the Earth’s solid structure. Proponents cite anomalies and unverified accounts, like Admiral Byrd’s alleged diaries, while critics emphasize the absence of credible evidence. The theory’s persistence reflects societal distrust and a fascination with hidden worlds, raising ethical concerns about misinformation and the misrepresentation of cultural myths. Looking forward, scientific advancements may further disprove the theory, but its cultural allure will likely endure in fiction and online discussions. The key lesson is the importance of critical thinking in evaluating extraordinary claims, especially in an era of rapid information spread. Balancing curiosity with evidence-based inquiry is essential to understanding such theories without falling into speculation. The Hollow Earth narrative highlights humanity’s enduring desire to explore the unknown, even as science maps the boundaries of what is possible. It serves as a reminder to approach fringe ideas with both openness and skepticism. Ultimately, the theory’s legacy lies in its ability to inspire wonder while underscoring the value of empirical truth.

Disclaimer: This article examines controversial theories and claims for educational purposes. Content does not constitute scientific or theological advice. Many theories discussed are rejected by mainstream science and lack empirical evidence. Think critically and conduct independent research. Questions? Contact editor@amen4jesus.com