Quick Insights

- The Apollo 11 mission, which landed humans on the moon in 1969, is one of NASA’s most celebrated achievements.

- Conspiracy theories claiming the moon landings were faked emerged shortly after the event and persist today.

- A 2021 study showed that 10% of Americans believe the moon landings were staged, up from 6% in 2020.

- NASA has provided extensive evidence, including lunar rocks and laser reflectors, to counter hoax claims.

- Social media platforms like X have amplified these theories, especially with recent Artemis mission announcements.

- Experts consistently debunk hoax claims, citing the overwhelming scientific evidence supporting the landings.

What Are the Basic Facts of the Moon Landing Hoax Theory?

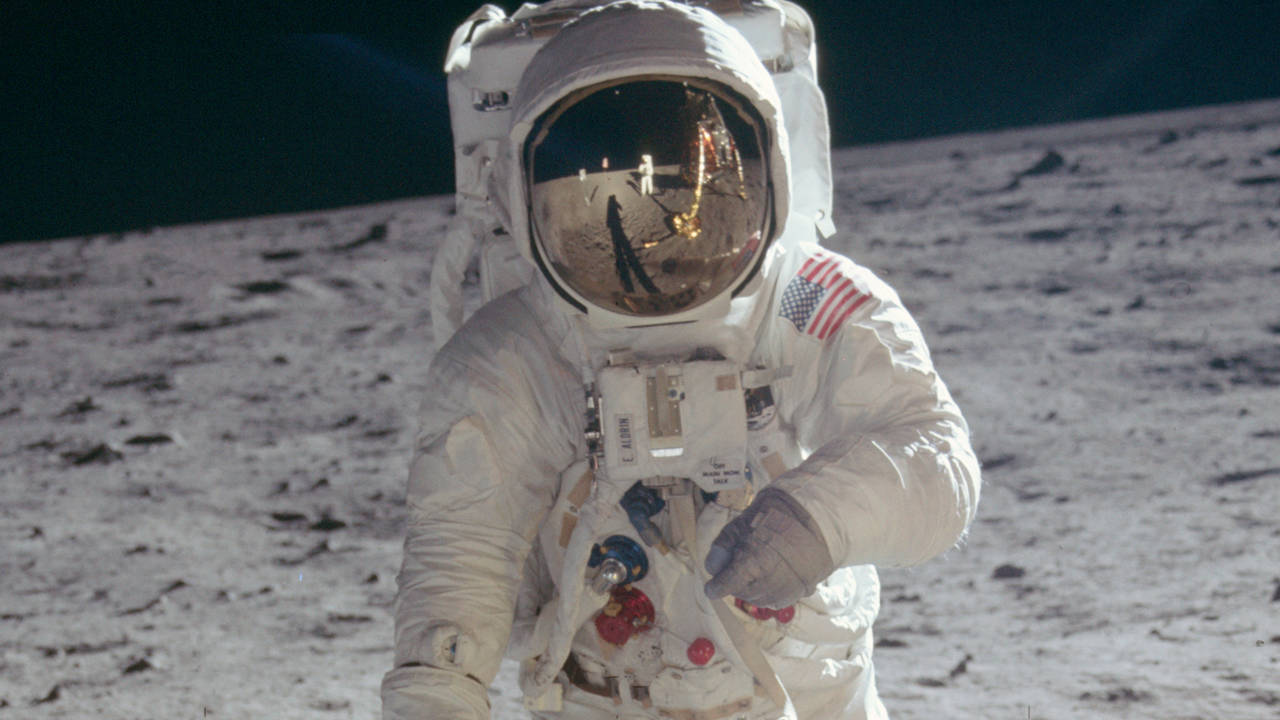

The Apollo 11 mission, launched on July 20, 1969, marked the first time humans set foot on the moon, with astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin making history. NASA conducted six successful moon landings between 1969 and 1972, involving 12 astronauts and bringing back 382 kilograms of lunar material. Despite this, conspiracy theories claiming the landings were faked have persisted for decades. These theories suggest NASA staged the missions in a studio to win the Cold War space race against the Soviet Union. Proponents point to perceived inconsistencies in photographs, such as the “waving” American flag or missing stars in images, as evidence of a hoax. A key figure in starting these claims was Bill Kaysing, a former technical writer for a NASA contractor, who published a book in 1976 alleging the landings were fabricated. His work laid the foundation for many modern arguments. Public opinion varies, with polls indicating 5-10% of Americans and up to 57% of Russians question the official account. The rise of the internet and social media has fueled these theories, with platforms like X hosting debates, especially after NASA’s Artemis II mission details were announced in 2025. NASA has consistently refuted these claims, pointing to physical evidence and independent observations as proof of the landings’ authenticity.

The persistence of the hoax theory is notable given the scale of evidence supporting the moon landings. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter captured images of the landing sites in 2011, showing descent stages and astronaut tracks. Retroreflectors placed on the moon by Apollo missions are still used by observatories to measure the Earth-moon distance with precision. Independent tracking by the Soviet Union, a rival at the time, confirmed the missions’ success, as did congratulatory messages from Soviet officials. Conspiracy theorists often argue that the Van Allen radiation belts would have been lethal to astronauts, but NASA counters that the spacecraft’s shielding and trajectory minimized exposure. The sheer number of people involved—over 400,000 workers—makes a coordinated cover-up highly improbable. Recent posts on X have reignited skepticism, with some users joking about “better CGI” for Artemis missions, reflecting ongoing distrust. The hoax theory thrives on selective interpretation of visual evidence, ignoring the broader scientific consensus. NASA’s transparency, including public access to lunar samples, further undermines the hoax narrative. Despite this, the theory remains a cultural phenomenon, often tied to broader mistrust in institutions.

What Is the Historical Context of the Moon Landing Conspiracy?

The Apollo program unfolded during the Cold War, a period of intense rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. The space race was a symbolic battleground, with both nations aiming to demonstrate technological and ideological superiority. President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 pledge to land a man on the moon by the decade’s end set a high-stakes goal for NASA. The successful Apollo 11 landing in 1969 was a major propaganda victory for the U.S., broadcast live to millions worldwide. However, the era’s political climate, marked by distrust in government due to events like the Vietnam War and Watergate, created fertile ground for skepticism. Bill Kaysing’s 1976 book, We Never Went to the Moon, capitalized on this mistrust, alleging NASA lacked the capability to achieve the landings and staged them instead. His claims resonated with a public already questioning official narratives. The theory gained traction in popular culture, with films like Capricorn One (1978) depicting a faked Mars mission, reinforcing the idea of government deception. The internet later amplified these ideas, allowing conspiracy theorists to share videos and images widely. By the 2000s, platforms like YouTube hosted content claiming photographic anomalies proved a hoax, despite scientific rebuttals.

The historical context also includes NASA’s own challenges in addressing public skepticism. In 2001, NASA issued a detailed response to hoax claims, citing lunar rocks, retroreflectors, and independent tracking as evidence. The agency faced a dilemma: engaging with conspiracies risked legitimizing them, while ignoring them allowed misinformation to spread. The 1970s loss of original Apollo 11 footage, though later restored digitally, fueled speculation about a cover-up. Cultural factors, like the rise of anti-establishment sentiment, kept the theory alive. In the UK, a 2012 poll found 12% of people believed the landings were faked, while a 2018 Russian poll reported 57% skepticism, reflecting anti-Western biases. The theory’s endurance highlights a broader trend of questioning scientific achievements, seen in later conspiracies about climate change or vaccines. NASA’s Artemis program, announced to return humans to the moon, has reignited these debates, with social media amplifying doubts about why landings haven’t occurred since 1972. The historical distrust in institutions continues to shape how these theories are received. Understanding this context reveals why the hoax narrative persists despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

What Are the Key Arguments For and Against the Hoax Theory?

Conspiracy theorists argue that photographic and video evidence from the Apollo missions contains anomalies proving the landings were staged. They point to the American flag appearing to “wave” in a vacuum, shadows at inconsistent angles, and the absence of stars in photos as signs of studio filming. Some claim the Van Allen radiation belts would have killed astronauts, suggesting NASA lacked the technology to protect them. Theorists like Jay Weidner have alleged that director Stanley Kubrick was hired to fake the footage, citing his film 2001: A Space Odyssey as evidence of his capability. Others highlight the lack of a visible crater under the lunar lander or claim reflections in astronaut visors show studio lights or crew members. These arguments often rely on visual analysis amplified by social media, where edited images or videos gain traction. A 2021 University of Miami study noted a rise in believers, from 6% to 10% of Americans, showing the theory’s growing appeal. On X, users recently questioned why NASA’s Artemis II mission won’t land on the moon, seeing it as evidence of ongoing deception. Such claims often dismiss scientific explanations in favor of intuitive skepticism. The emotional appeal of uncovering a “hidden truth” drives much of the theory’s popularity.

In contrast, scientists and NASA provide robust evidence supporting the landings. Lunar rocks brought back have a unique chemical composition, distinct from Earth’s, and have been studied by independent researchers worldwide. Retroreflectors placed on the moon allow laser ranging from Earth, with observatories like the McDonald Observatory detecting signals since 1971. The Soviet Union, a rival, tracked the missions and never disputed their success. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter photographed landing sites, showing equipment and tracks. The involvement of 400,000 workers and multiple independent organizations makes a conspiracy of this scale implausible. Experts explain that the flag’s appearance is due to the lack of atmosphere, causing it to hold its shape, not wave. Shadows in photos follow lunar lighting physics, and stars are absent due to camera settings prioritizing bright foregrounds. The Van Allen belts were navigated quickly, with shielding protecting astronauts from harmful radiation. These counterarguments, grounded in verifiable data, consistently debunk hoax claims, yet skepticism persists among those distrustful of authority.

What Are the Ethical and Social Implications of the Hoax Theory?

The moon landing hoax theory raises ethical questions about the spread of misinformation and its impact on public trust. By questioning a well-documented scientific achievement, the theory undermines the credibility of institutions like NASA, which rely on public support for funding and legitimacy. This distrust can extend to other scientific fields, such as climate science or medicine, fostering a broader anti-science sentiment. The theory’s persistence, amplified by social media, highlights the ethical responsibility of platforms to address misinformation without stifling free speech. Conspiracy theorists often present themselves as truth-seekers, but their selective use of evidence can mislead audiences, particularly younger generations exposed to viral content on platforms like TikTok. The 2023 Scientific American article noted that such theories pave the way for more dangerous beliefs, like anti-vaccine conspiracies, which have tangible public health consequences. The ethical challenge lies in balancing open discourse with the need to correct false narratives. Socially, the theory taps into a desire for hidden knowledge, appealing to those who feel alienated by complex systems. This can deepen societal divides, as believers and skeptics talk past each other. Addressing these implications requires fostering critical thinking without dismissing public skepticism outright.

The social impact of the hoax theory also reflects broader cultural dynamics. It thrives in environments of low institutional trust, as seen in historical events like Watergate or modern political polarization. The theory’s appeal lies in its simplicity, offering an alternative narrative that doesn’t require scientific literacy. This can marginalize scientists and educators, who face the burden of repeatedly debunking claims. The theory also perpetuates a form of cultural rebellion, where questioning established history becomes a badge of independence. However, this rebellion can erode collective achievements, diminishing the Apollo program’s role as a symbol of human ingenuity. The spread of hoax claims on X, especially after Artemis II announcements, shows how social media can amplify fringe views, creating echo chambers. Ethically, promoting such theories without evidence risks harming public discourse by prioritizing sensationalism over facts. Efforts to counter this, like NASA’s public engagement with lunar samples, aim to rebuild trust but face challenges in reaching skeptical audiences. The theory’s endurance underscores the need for better science communication to bridge gaps between experts and the public.

What Does This Mean for the Future of Space Exploration?

The moon landing hoax theory poses challenges for NASA’s future missions, particularly the Artemis program, which aims to return humans to the moon. Public skepticism, amplified by social media, could undermine support for costly space endeavors. Recent X posts questioning why Artemis II won’t land on the moon reflect ongoing distrust, potentially pressuring NASA to prioritize public relations over scientific goals. If a significant portion of the public views past achievements as fake, securing funding for new missions becomes harder. The 2021 University of Miami study showing rising belief in the hoax suggests this issue may grow, especially as younger audiences encounter conspiracy content online. NASA’s transparency, such as sharing Artemis mission details, aims to counter this, but addressing viral misinformation requires more proactive engagement. The agency may need to invest in educational outreach to rebuild trust, particularly among skeptical demographics. Future missions could face scrutiny over every image or video, with conspiracies potentially overshadowing scientific milestones. This dynamic risks diverting resources from exploration to myth-busting. The challenge is to maintain public enthusiasm for space while combating false narratives.

Looking ahead, the hoax theory’s persistence could shape how space agencies communicate with the public. NASA’s experience with Apollo suggests that ignoring conspiracies allows them to fester, while direct engagement risks amplifying fringe voices. The Artemis program, with its goal of sustainable lunar exploration, offers a chance to demonstrate transparency through live streams, open data, and public access to mission artifacts. However, the theory’s cultural staying power, seen in films like Fly Me to the Moon (2024), indicates that conspiracies will likely persist regardless of evidence. This could influence international collaboration, as global partners may face similar skepticism in their countries. The theory also highlights the importance of media literacy in education, as future generations will need tools to evaluate online claims critically. Space exploration’s success depends on public support, which hinges on trust in scientific institutions. By addressing hoax theories head-on with clear, accessible evidence, NASA can pave the way for renewed excitement about lunar exploration. The lessons from Apollo’s legacy will be crucial in navigating this challenge. Ultimately, the future of space exploration relies on balancing scientific ambition with effective public communication.

Conclusion and Key Lessons

The Apollo moon landing hoax theory, despite being thoroughly debunked, remains a persistent challenge to NASA’s legacy and future endeavors. The theory emerged from a mix of Cold War-era distrust, selective interpretation of visual evidence, and the amplifying power of the internet and social media. Key evidence, like lunar rocks, retroreflectors, and independent tracking, confirms the landings’ authenticity, yet 5-10% of Americans and higher percentages globally still question the official account. The theory’s endurance reflects broader societal issues, including mistrust in institutions and the appeal of alternative narratives. Ethically, it raises concerns about misinformation’s impact on public trust and scientific progress, while socially, it highlights the need for better science communication. For the future, NASA must address skepticism proactively to maintain support for programs like Artemis.

The key lesson is that scientific achievements, no matter how monumental, are vulnerable to misinformation in an era of rapid information sharing. Public trust requires ongoing engagement, transparency, and education to counter false narratives. The Apollo hoax theory serves as a case study in how conspiracies can shape perceptions of history and science, urging agencies to prioritize clear communication. As space exploration advances, fostering critical thinking and media literacy will be essential to sustaining public enthusiasm and trust. The moon landings remain a testament to human achievement, but their legacy underscores the ongoing need to bridge the gap between science and society.

Disclaimer: This article examines controversial theories and claims for educational purposes. Content does not constitute scientific or theological advice. Many theories discussed are rejected by mainstream science and lack empirical evidence. Think critically and conduct independent research. Questions? Contact editor@amen4jesus.com