Quick Insights

- Incorruptibility refers to the preservation of a saint’s body after death, defying natural decomposition.

- The Catholic Church has documented over 100 saints whose bodies remain partially or fully intact.

- St. Teresa of Avila’s body, recently examined in 2024, was found remarkably preserved 442 years after her death.

- Incorruptibility is no longer considered a miracle by the Vatican but remains a point of fascination for believers.

- Some cases, like Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster’s, draw pilgrims despite no official sainthood process.

- Scientific explanations often attribute preservation to natural conditions, while the Church emphasizes spiritual significance.

What Are the Basic Facts of Incorruptibility?

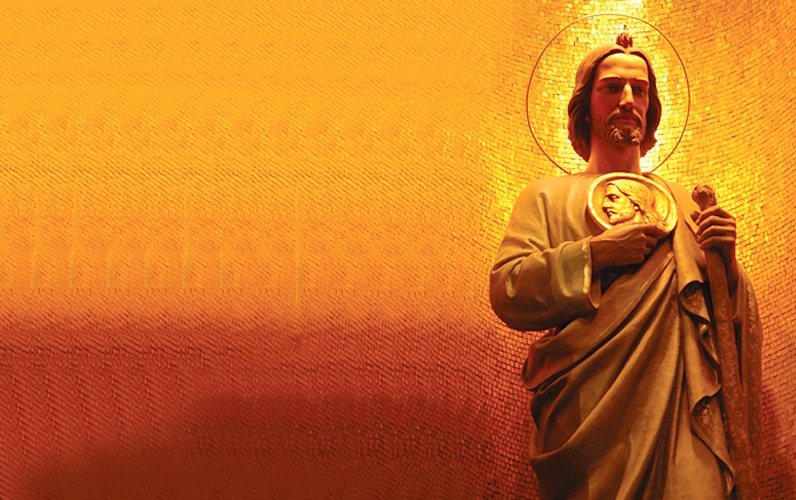

Incorruptibility in the Catholic tradition describes bodies of certain saints that do not decay as expected after death. The Church has recorded over 100 such cases, with examples spanning centuries, from St. Cecilia in the 2nd century to more recent figures like St. Bernadette Soubirous, who died in 1879. A notable recent case involves St. Teresa of Avila, a 16th-century Spanish nun whose tomb was opened in 2024, revealing her body in a remarkably preserved state, as reported by the Diocese of Avila. Her remains, last examined in 1914, showed minimal decay, retaining features like an eyelid and nasal tissue. Another case, Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster, an African American nun who died in 2019, was exhumed in 2023 and found with little decomposition, sparking widespread interest. These discoveries often lead to public veneration, with pilgrims visiting sites like Alba de Tormes in Spain or Gower, Missouri. The Catholic Church does not require incorruptibility for sainthood, and the phenomenon is not officially deemed miraculous. Some bodies, like that of Blessed Carlo Acutis, are displayed with silicone masks due to partial decay. The preservation process varies, with some bodies naturally intact and others aided by wax or other treatments. These cases continue to captivate both the faithful and skeptics, raising questions about their significance.

The fascination with incorrupt bodies stems from their perceived defiance of natural processes. Historically, when a body was found intact years after burial, it was often seen as a sign of holiness. Today, the Church takes a cautious approach, noting that preservation alone does not confirm sanctity. For instance, St. Teresa’s body was studied by researchers who noted medical details, such as heel spurs, indicating chronic pain during her life. Sister Wilhelmina’s case, while not part of a sainthood process, has drawn attention for its cultural significance, particularly among Black Catholics. The Church investigates these cases to rule out intentional preservation, such as embalming, which was not always common in earlier centuries. Some bodies, like St. John of the Cross, remain supple despite centuries in simple graves. Others, like St. Victoria, have wax enhancements to maintain their appearance. The phenomenon varies widely, with some saints showing only partial preservation, such as St. Anthony of Padua’s tongue. These cases fuel both devotion and debate about their meaning.

What Is the Historical Context of Incorruptibility?

The belief in incorruptibility dates back to early Christianity, when death and decay were poorly understood. In the first century, the Church began canonizing saints, and preserved bodies were often seen as miraculous, especially in an era when mummification was rare outside Egypt. By the Middle Ages, incorruptibility became associated with divine favor, as most bodies turned to dust in simple graves. Early records, like those of St. Cecilia, describe her body found intact in 822, centuries after her martyrdom. This phenomenon was documented in Joan Carroll Cruz’s 1977 book, “The Incorruptibles,” which lists 102 saints or blesseds with preserved remains. The Church historically viewed these cases as potential signs of sanctity, though not definitive proof. During the Bolshevik Revolution, Russian authorities claimed incorrupt bodies were wax figures to discredit the Church, highlighting the phenomenon’s cultural weight. Over time, the Vatican’s stance evolved, with modern science prompting a more skeptical view. By 2018, the Vatican acknowledged that some “incorrupt” bodies had been preserved through natural or artificial means. Despite this, the faithful continue to venerate these relics as symbols of eternal life.

The historical context also reflects changing burial practices and scientific understanding. In medieval times, bodies were often buried in dirt or wooden coffins, making preservation unusual. Cases like St. Rita of Cascia, whose body remains intact since 1457, stood out against this backdrop. The Church investigated these cases to ensure no human intervention, like embalming, was involved. By the 20th century, advances in forensic science revealed that some preservation could result from environmental factors, such as dry soil or low oxygen. Joan Carroll Cruz argued that many incorrupt bodies lacked the rigidity of mummified remains, suggesting a unique phenomenon. However, the Vatican’s 1975 preservation efforts, led by Monsignor Gianfranco Nolli, showed that some bodies were maintained with oils or herbs. This shift reduced the emphasis on incorruptibility as a miracle. Still, the tradition persists, with modern cases like St. Charbel Makhlouf, exhumed in 1898, accompanied by reports of fragrant scents. These historical shifts frame the ongoing debate between faith and science.

What Are the Key Perspectives on Incorruptibility?

The Catholic Church and its followers view incorruptibility as a spiritual sign, not a requirement for sainthood. Believers see it as evidence of God’s power over nature, pointing to the resurrection of the body, as noted in the Catechism (CCC 988-1019). Pilgrims flock to shrines, like St. Bernadette’s in Nevers, France, seeking spiritual connection or healing. Father William Saunders has described incorruptibility as a reflection of a saint’s holy life, though not definitive proof. Some theologians argue it inspires faith in eternal life, as seen in the veneration of St. Teresa’s body in 2024. However, the Church cautions against overemphasizing physical preservation, noting that many saints’ bodies decay normally. Cases like Blessed Carlo Acutis, whose body uses a silicone mask, show that veneration often relies on symbolic representation. The faithful accept partial preservation, like St. Anthony’s tongue, as meaningful. This perspective prioritizes spiritual significance over scientific explanation. For many, these bodies are tangible links to the divine, fostering devotion.

Skeptics and scientists offer a contrasting view, attributing incorruptibility to natural or human factors. Msgr. Robert Sarno, a retired Vatican investigator, has stated that preservation is often natural, not miraculous, citing conditions like dry environments or low oxygen. Some bodies, like St. Victoria’s, are enhanced with wax, raising questions about authenticity. Critics argue that the Church historically promoted these cases to bolster faith, sometimes ignoring evidence of preservation techniques. For example, the Vatican’s 1975 preservation efforts used oils and herbs on some relics. Secular outlets, like The Herald, compare incorrupt bodies to “McDonald’s hamburgers,” suggesting natural processes explain their condition. Forensic studies of St. Teresa’s body in 2024 noted environmental factors in her tomb that could slow decay. Skeptics also point to cases where bodies, like St. John of the Cross’s, decomposed after flooding, undermining claims of divine intervention. This perspective emphasizes empirical evidence over spiritual interpretation. The debate between these views remains unresolved, with both sides citing compelling evidence.

What Are the Ethical and Social Implications?

Incorruptibility raises ethical questions about the treatment of human remains. Displaying bodies, like St. Teresa’s in Alba de Tormes, draws pilgrims but can seem voyeuristic to critics. The Herald argues that such displays exploit the dead, denying them dignified burial. The Church counters that veneration respects the body as a temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Corinthians 6:19). Cases like Sister Wilhelmina’s highlight cultural significance, especially for Black Catholics, as her preservation underscores the contributions of African American religious figures. This can foster inclusivity within the Church, as noted by historian Shannen Dee Williams. However, the practice risks sensationalism, with media coverage sometimes focusing on the macabre over the spiritual. The Church must balance devotion with sensitivity to avoid trivializing sacred relics. Ethical concerns also arise when preservation techniques, like wax or silicone, are not disclosed, potentially misleading the faithful. These displays shape Catholic identity, reinforcing beliefs about the afterlife while sparking debate about respect for the deceased.

Socially, incorrupt bodies influence communities by drawing pilgrims and boosting local economies. Sites like Lourdes, where St. Bernadette’s body is displayed, attract millions annually, supporting tourism and local businesses. Sister Wilhelmina’s case in Missouri has brought attention to Black Catholic history, fostering dialogue about race and faith. However, the phenomenon can deepen divisions between believers and skeptics, with some viewing it as superstition. The Church’s cautious stance reflects an effort to maintain credibility in a scientific age. Public fascination, as seen in the 2024 display of St. Teresa’s body, shows the enduring appeal of these relics. Yet, ethical concerns persist about whether such displays prioritize spectacle over reverence. The Church’s decision to de-emphasize incorruptibility as a miracle aims to focus on spiritual virtues. Social media amplifies these stories, with posts on X highlighting St. Teresa’s preservation, but also fueling skepticism. The phenomenon thus shapes both faith communities and broader cultural conversations.

What Does This Mean for the Future?

The future of incorruptibility in the Catholic Church hinges on balancing tradition with modern scrutiny. As science advances, more cases may be explained by natural factors, reducing their perceived miraculous nature. The Church’s shift away from viewing incorruptibility as a miracle suggests a focus on spiritual legacy over physical preservation. Future canonizations, like that of Sister Wilhelmina, may prioritize historical impact, especially for marginalized groups, over bodily condition. Pilgrimage sites will likely remain popular, sustaining cultural and economic benefits for communities. However, the Church may face pressure to clarify preservation methods to maintain transparency. Cases like St. Teresa’s, studied with modern forensics, could set a precedent for rigorous investigation. This might reshape how relics are presented, with greater emphasis on their symbolic role. Social media will continue to amplify these stories, as seen with posts on X about St. Teresa, but also invite skepticism. The Church must navigate these dynamics to preserve the phenomenon’s spiritual weight.

The phenomenon also raises questions about faith in a scientific age. As forensic techniques improve, the Church may need to redefine incorruptibility’s role in devotion. Future discoveries, like Sister Wilhelmina’s, could inspire new generations, particularly in underrepresented communities. Yet, the risk of sensationalism grows with media coverage, potentially overshadowing the saints’ lives. The Church might emphasize educational efforts, highlighting virtues over physical relics. Transparency about preservation techniques could build trust with skeptics. The global reach of pilgrimage sites suggests that incorruptibility will remain a draw, but its significance may shift toward cultural heritage. The Church’s cautious approach, as seen in its response to St. Teresa’s case, reflects an effort to align tradition with modernity. Debates on X and other platforms will likely continue, shaping public perception. Ultimately, incorruptibility’s future lies in its ability to inspire faith while addressing scientific and ethical challenges.

Conclusion and Key Lessons

Incorruptibility remains a captivating aspect of Catholic tradition, blending faith, history, and science. The cases of St. Teresa of Avila and Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster highlight its enduring appeal, drawing pilgrims and sparking debate. The Church’s shift away from viewing preservation as a miracle reflects a response to scientific scrutiny, emphasizing spiritual virtues instead. Historically, these bodies inspired awe in an era of limited scientific knowledge, but today, they face skepticism from those who cite natural or artificial preservation. The ethical tension between veneration and respect for the dead underscores the need for transparency in how relics are presented. Socially, incorruptibility fosters community and cultural identity, particularly for groups like Black Catholics, while economically supporting pilgrimage sites.

Key lessons include the importance of balancing tradition with modern understanding. The Church must navigate scientific explanations without diminishing the spiritual significance of these relics. Transparency about preservation methods can maintain credibility, while the cultural impact of figures like Sister Wilhelmina highlights the need for inclusivity in Catholic narratives. The phenomenon’s future depends on its ability to inspire faith while addressing ethical and scientific concerns. As social media amplifies these stories, the Church faces both opportunities and challenges in shaping public perception. Ultimately, incorruptibility serves as a reminder of the Catholic belief in eternal life, even as its physical manifestations are questioned.

Disclaimer: This article examines controversial theories and claims for educational purposes. Content does not constitute scientific or theological advice. Many theories discussed are rejected by mainstream science and lack empirical evidence. Think critically and conduct independent research. Questions? Contact editor@amen4jesus.com